GUIDE TO OUTSOURCING

August 1, 2006

|

During an outsourcing project, the need to transfer a great deal of information efficiently also drives the need for peer-to-peer collaboration. Every medical device product benefits from the contributions of many minds as it moves from design to production, or from manufacturing site A to manufacturing site B. If design is done in-house and production is done outside—or site A belongs to the OEM and site B belongs to a contract manufacturer—then the volume of information to be transferred is tremendous. Great care is required to handle this transfer well. Therefore, effective communication techniques and carefully crafted project management techniques are critical to successful outsourcing.

Outsourcing Is Here to Stay

Outsourcing is securely rooted in medical manufacturing. Over the last couple of decades, the demand for contract manufacturing of medical products has exploded. There are multiple reasons for such growth (see Table I). Companies continue to focus their efforts on key skills, such as R&D or marketing. These OEMs must have experts to build and provide services to turn those skills into marketable products. The relationship between an OEM and a contract manufacturer is key to ensuring the success of those products. And OEMs must be aware of the intricacies of that relationship.

You're Hiring

|

Table I. (click to enlarge) The continued proliferation of outsourcing in medical manufacturing stems from the need to bring innovation to the market quickly and economically. |

There is a tendency to think about outsourcing, and contract work in general, as a temporary arrangement, easily begun with a few signatures on a contract and easily ended with a letter of termination.1 Indeed, this rapid start-up and easy shutdown is precisely one of its positive features. But in reality, an OEM is hiring resources as surely as though it had placed a want ad, winnowed through a stack of resumes, held several interviews, and then welcomed the winning candidate into a cubicle.

OEMs should view hiring contractors as seriously as they would hiring a permanent employee. And using such a model helps OEMs to consider various steps in the introductory process in a practical fashion. For example:

• When hiring an employee, a company controls the new recruit's training. An OEM must take the lead when new talent is brought to products and processes.

• An employer is especially careful to introduce a new person to the medical conditions that its products address and the practitioner community that it serves.

• An employer eases a new employee into an ongoing project. The more critical an employee's role, the more an employer should ensure thorough mentoring and backgrounding.

• A savvy employer listens carefully to a new employee's observations, because a new recruit is in a unique position to see possibly irrational, wasteful, or illogical elements of a program.

An OEM must take the same care and consideration when hiring an outsourcer as it would with hiring a full-time employee. Both decisions reflect on the perceived quality of the company and the success of products in the market.

Encapsulate, then Transfer

Sidebar: The Art of Encapsulation |

Successful outsourcing simply takes the employee concepts and objectifies them into project beginnings, middles, and ends. Doing so encapsulates each concept that must be transferred to the contract manufacturer (see the sidebar, “The Art of Encapsulation.”) Encapsulation depends on best practices for knowledge and technology transfer.

A number of contract manufacturers, especially those that aspire to become the manufacturing arm of the OEM, rather than simply being a contractor, have developed comprehensive project management skills. And, the more comprehensive these skills are, the better. The best contract manufacturers can offer technological support for projects that include drawing and document distribution and control, day-and-night access to project timelines and tasks, meeting technologies for face-to-face and virtual conferencing, dashboards for visibility into manufacturing and distribution activity, secure e-mail, and even chat facilities.

But that is not always enough. Besides having well-defined stages or phases, a contractor should have an attitude that says “the gate is closed on later stages until earlier stages are complete.”

A key determinant in the flow of an outsourcing project is the life cycle of the product. The transfer of a mature product is different from the commissioning of a new product. Focus for a mature product is generally cost related. For new products, however, even though cost is also a factor, the primary emphasis may be on reducing the time needed to create a product that meets quality standards.

With Maturity Comes Wisdom. Mature products tend to be easier to encapsulate into project stages than developmental products. A mature product's tooling, materials specifications, and manufacturing and quality procedures are generally well established. Formal specifications, step-by-step instructions, and critical quality areas are relatively easily learned when the product and its processes have been in place for many years.

If tooling is involved, its transfer from previous sites to the new site may present the most challenging logistical and operational problems in the project. For molded products, tooling almost certainly will have been developed for the machines on the original site. Equipment at the new site may or may not have working dimensions that are fully compatible with the earlier tooling.

Additionally, especially in processes such as thermoplastic molding, the aesthetics and dimensions (and potentially the functionality of the product) are the result of a complex interaction among materials, materials handling, tooling, molding parameters, postmolding handling, and the like. A contracting partner should have a formal protocol that covers tool setting and first-article production.

Finally, regarding tooling, a logistics plan needs to accommodate the loss of production during the time that tooling is unavailable between shutdown at the old site and start-up at the new.

Challenges can arise if materials and components are to be sourced locally to the new site. Fortunately, materials and component infrastructures in such key low-cost manufacturing regions as China are strong, helping to minimize logistical problems and potentially lowering costs even further. Assuming an outsourcing partner is careful to qualify its suppliers, it may even have a wider range of choices than Western manufacturing regions.2

A consideration sometimes overlooked is the manufacturing layout. When cost is a primary consideration, lean manufacturing principles have a proven track record for decreasing costs and increasing efficiencies. Both the flow of work through the plant floor and the arrangement of machines and assembly stations are closely scrutinized in lean manufacturing. An OEM clearly wants to find a manufacturing partner that can configure modular assets into a line that fully accommodates the product. Such a solution is far superior to that of trying to shoehorn a product into a fixed, less-than-efficient workspace.

The final step in moving a mature product into contract manufacturing is an explicit, detailed qualification and validation process. An OEM must apply due diligence to ensure that personnel, equipment, materials, and processes all coalesce into a product made to specification. There should be no discernable difference between the product made at the OEM's site and that of the contract manufacturer.

Developmental Products. If transfer of tooling and manufacturing procedures is the key element in projects for mature products, the two key elements for developmental products are the communication process and the project management infrastructure. There tend to be many changes as a product exits design and enters production. Any significant disconnect between an OEM and a manufacturer during this transition can bring unhappy outcomes. For example, OEMs should take care to develop manufacturing procedures for the product's latest revision level. Any last-minute substitution of purchased components (while easily implemented in engineering) can significantly disrupt the supply chain for the contract manufacturer.

|

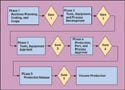

Figure 1. (click to enlarge) Stage-gate or phased projects are characterized by project phases that have been set up to provide necessary prerequisites for follow-on activities. Steps must be formally signed off at the end of a given phase, with all key details complete, before the project moves to the next phase. |

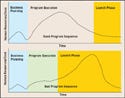

Project management is a well-established discipline with many workable methodologies for developing measurable milestones, assigning task responsibilities, and defining deliverables. One refinement used is a stage-gate approach. It provides a safety net (see Figure 1). In this process, a project cannot move to a new phase until mutually agreed details in the current phase are completed and signed off. The kicker is that the last detail completion in a technical project is extraordinarily difficult because people are often anxious to move on to new challenges instead of finishing the leftover tasks (see Figure 2). Despite that, both OEMs and outsourcers must install oversight on both sides to monitor the process and ensure completion.

|

Figure 2. (click to enlarge) Phased programs are more likely to result in a good program sequence (top), because problem areas are identified and resolved before launch. Otherwise, details may slide and problems may be unseen until a final (and often frantic) launch phase. Because the launch phase also encompasses critical manufacturing procedures, quality protocols, cost, and other key elements, problem solving at this stage (bottom) can result in strained resources and missed details. |

Collaborative communication technologies should provide means for peer-to-peer discussion, as well as for electronic transfer of drawings, documents, and change orders. Web-based technologies may be especially helpful because they can be accessed at any time, from any place. An element of this, which is sometimes overlooked, includes training contract manufacturing personnel to use the OEM's drawing conventions, markup symbols, terminology, and objectives and structures of manufacturing and quality procedures. Such training helps to minimize miscommunication or misunderstanding of a project's goals or direction.

Validation of the supply chain, approval of manufacturing layouts, validation of manufacturing equipment, and validation of quality instrumentation and procedures all are similar to corresponding elements in projects for mature products. But there is an important difference. In the developmental projects, OEMs have the opportunity to benefit from the contract manufacturer's experience by tapping that manufacturer's expertise early in the process.3 Such collaboration can help ensure the manufacturability of the product, as well as potentially reduce the time to reach acceptable quality in first-article production.

Dimensions, functionality, efficacy, and safety all must be validated during prototype and first-article production stages, of course. Actual costs of production as well as actual times for distribution should begin to emerge in this stage as well.

Production and Review

Once the product moves into full production, it is time for the final project phase: the supplier review. There may be a critical pitfall here, because hopefully, by this stage, personnel from the OEM have developed many close relationships with personnel at the contract manufacturer. The strong relationships that have been developed may have to be put aside for an end-of-project evaluation to ensure objectivity.

For this phase, commercial construction projects use a tool called a punch list. Building owners, major contractors, and building engineers tour the structure, floor by floor, calling out anything that deviates from the as-designed structural and aesthetic fabric of the building. These punch items are then brought to specification. The wrap-up of any outsourcing project can benefit from a similar punch list.

The punch list varies based on the product, but at least it should include detailed measurements of quality and an assessment of intangibles. Medical device OEMs should consider the following:

• Strength.

• Integrity.

• Functionality.

OEMs should also consider aesthetics such as whether the glue or weld joints are attractive or sloppy, whether the hot stamping or decoration is crisp, how the product is boxed (is it neatly stacked or just tossed in?), and how the molded components appear (do they have good color and appearance, or do they seem crude?)

Even more importantly, OEMs should consider the outsourcer's initiative and responsiveness to requests. Have they offered cogent, value-added ideas? Are they quick and creative problem solvers?

Once the punch list is resolved, the OEM has a final, ongoing set of activities: control over formal change processes, revalidations, ratification of moves implemented by the manufacturer to effect continuous improvement, and formal reviews. Just as any good employee would, a good contract manufacturer will want to know in what areas it is doing well and where it needs to improve.

Gehman is a freelance writer and marketing consultant based in Framingham, MA with experience in Class III cardiology devices. He can be reached via e-mail at [email protected].

References

1. David A Vogel, “Good Contracts Lead to Good Relationships,” MD&DI Guide to Outsourcing 27, no. 8 (2005): S-50–S-60.

2. Ames Gross and Caroline Tran, “Medical Manufacturing in Asia: An Update,” Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry 25, no. 5 (2003): 104–111.

3. Robert R Andrews, “10 Reasons to Outsource Design and Development,” MD&DI Guide to Outsourcing 28, no. 3 (2006): S-32–S-42.

Copyright ©2006 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like