Questionable relationships spark an inquiry from several congressmen. Here is von Eschenbach’s chance to show FDA’s transparency.

January 1, 2008

WASHINGTON WRAP-UP

|

He isn't getting much credit yet for accomplishments at FDA, but Commissioner Andrew von Eschenbach deserves at least some recognition for propelling the cause of greater transparency where agency conflicts of interest are concerned. He may not, however, realize just how much there is to this topic.

At the end of October, FDA published a draft guidance on the disclosure of financial interests by members of all FDA advisory committees. A few weeks later, the agency published another on the proper way such members should vote on products under review. These are small but positive steps on the road to more transparency and, by inference at least, accountability.

|

Barton wants answers regarding CDRH's enforcement actions. |

FDA advisory committee members are officially special government employees and, as such, have to make public disclosures about the regulated companies with which they have been financially involved. Permanent government employees are, of course, prohibited from having these sorts of financial relationships with the companies they regulate. But FDA employees are not required to disclose conflicts of interest before acting for or against a regulated company. Von Eschenbach will discover a very tangled web in this area, if he looks.

Minority House Energy and Commerce Committee members Joe Barton (R–TX) and Ed Whitfield (R–KY) asked von Eschenbach to do just that in November, addressing a decade of unsupervised and allegedly abusive CDRH enforcement actions against small device companies.

|

Whitfield questions FDA's dispute resolution practices. |

In a three-page letter citing an ongoing CDRH civil monetary penalties case, Barton and Whitfield asked the commissioner to “personally review how center directors monitor top disputes and controversies, and report back on management performance in this area, and whether any further steps or actions will be taken to improve dispute resolution and priority setting of enforcement resources.” They asked for a report from the commissioner by December 14, 2007. Although the letter did not mention TMJ Implants by name, the details described in the letter matched its case.

Dispute resolution is an area in which FDA has been fraught with internal and undisclosed conflicts of interest of the ethical and interpersonal kind. Barton and Whitfield wrote that they “question whether the greatest public health impact is being achieved by FDA pursuing a protracted dispute with a small company rather than using good-faith dispute resolution. The case involves a four-year-old dispute over a medical device firm not submitting 17 reports, for which FDA is seeking $10,000 per violation and $510,000 in total civil money penalties.”

The congressmen reminded von Eschenbach that they had written him in April on this issue and noted that FDA responded in late July. In that response, FDA deflected questions about whether FDA's commissioner has decided any appeal in the past 10 years, such as the appeal TMJI filed, in favor of the appellant and whether it has “mooted out” an appeal, as it did in TMJI's case, because of an intervening enforcement action.

|

Von Eschenbach has been asked to review top disputes. |

That's where FDA appears to have had an undisclosed conflict of interest. The staff attorney who advised the commissioner's office to turn back TMJI's appeal unconsidered, Vernessa Pollard, was reportedly then working on the development of a civil monetary penalties complaint against the Golden, CO–based company. That complaint was filed a few days later, after which action government rules would have prevented her from advising on the appeal.

Legally, it's not a conflict—but ethically? Pollard declined to answer a question on this that I e-mailed to her.

Small device companies whose ordeals are now legend have long histories at FDA of similar hidden, not-strictly-illegal conflicts of interest among agency personnel. “Stacked” advisory committees to achieve FDA staffers' desired results on a product are not unknown, for example.

Von Eschenbach's recent predecessors have tolerated these conflicts because the companies have lacked the resources and political connections to incite public outrage.

Now Barton and Whitfield are on a warpath over the same issue, giving their party's appointee at FDA, von Eschenbach, yet another chance to show his reformist mettle.

‘I Am a Violator' T-Shirt for Device Maker

As part of his punishment for manufacturing and selling an unapproved catheter, an Alabama device wholesaler was ordered in October to attend 24 hours of educational instruction while wearing a shirt that read: “I was convicted of violating the FDCA.”

Northern District of Alabama federal judge Karon O. Bowdre included this plea-agreement provision in sentencing the wholesaler. James Lee, 62, of Birmingham, AL, pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of violating the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. In addition to having probation for one year, he was ordered to pay a $2000 fine and attend AAMI classes as punishment for directing the manufacture and marketing of a cholangiography catheter in 2005 without obtaining FDA approval.

Lee operates Advanced Medical Systems, which was founded in 1977 and has three employees. The firm sells durable medical equipment as a wholesaler.

“Persons who sell medical devices must follow the regulations established by the Food and Drug Administration,” said U.S. Attorney Alice Martin. “Fortunately, there were no patients harmed by these unapproved catheters. Devices that have not been approved for sale potentially pose health risks for the general public.” An FDA Office of Criminal Investigations special agent conducted the investigation.

Waxman Quizzes FDA on Sprint Fidelis Leads

Congressman Henry Waxman (D–CA), chairman of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, is asking FDA for information on its approval of the recalled Medtronic Sprint Fidelis implantable cardiac defibrillator leads. In an October 22 letter to FDA commissioner Andrew von Eschenbach, Waxman said Medtronic estimates that 2.3% of patients receiving the leads will experience fractures in them.

“Some concerns have been raised about whether FDA required adequate preapproval testing for these heart-device components,” he wrote. He said he applauds FDA for promptly recognizing and taking steps to address “what is apparently a serious shortcoming in the agency's approval process for these devices.” Waxman asked for this specific information:

A chronology of agency actions related to approval of the Sprint Fidelis leads, including approval date, premarket approval (PMA) or supplement number under which the leads were approved, and any subsequent agency actions or approvals related to the leads.

How many of the 37 supplements listed for the Medtronic transvene lead system PMA address new system components, how FDA decided the Sprint Fidelis leads were a new component rather than a new device, and what distinguishes a new component from a new device.

A summary of the safety and effectiveness data on which FDA based approval of the Sprint Fidelis leads, with an explanation of why the information is not on FDA's Web site as it is for many other PMA devices, and an explanation of why FDA did not require Medtronic to submit clinical trial data to support the safety and effectiveness of the leads.

The process by which FDA approves all defibrillator leads and an explanation of whether FDA would approve a defibrillator lead under a distinct PMA or as a supplement to a PMA for another device.

When and how FDA first became aware of the potential fracture problem and when FDA first proposed that the company take action, as well as a description of the events leading to the voluntary recall, including any FDA communications with the company about it.

The number and types of adverse events reported by month to FDA since the introduction of the leads and whether all adverse event reports related to fracture problems were submitted to FDA in a timely manner.

After problems with Guidant defibrillators, whether FDA created guidances or policies for device oversight and whether there are any guidances or policies on approving defibrillator leads.

Whether Medtronic provided FDA with data from its returned-product analysis and system longevity studies and when the data were turned over to FDA.

Whether FDA reviewed any direct-to-consumer ads for the Sprint Fidelis leads or any Medtronic device including such leads.

When I asked FDA about the 400 million repetitions of a bending motion that were performed on the Sprint Fidelis leads prior to approval, the agency's press office e-mailed the following statement: “Medtronic conducted the testing and submitted the results to FDA as part of their supplement requesting approval for the Sprint Fidelis lead. These tests are done on most leads before marketing to evaluate a certain portion of the lead, the distal (farthest) end from the defibrillator, for its fatigue resistance. When changes are made to that section of the lead, we ask companies to rerun the test. If a lead is the same as its immediate predecessor at that location (the far end) we don't require that testing to be rerun. The testing that is done is based on the kinds of changes the company is requesting.”

FDA Writes on Unretrieved Device Fragments

FDA says it receives more than 1000 adverse event reports each year related to unretrieved device fragments (UDFs) left in patients after a device fails and either no attempt was made to retrieve it or an attempt was unsuccessful. A common cause of UDFs is catheter and guidewire fractures, writes FDA nurse consultant Robert Fischer in the November issue of Nursing 2007.

“Besides occlusion, UDFs can lead to tissue injury and other complications. For example, metallic fragments within the body may potentially move or become warm during magnetic resonance imaging,” Fischer writes. “If the metal is close to a vital organ or blood vessel, it may cause serious complications. According to reports in the literature, some patients don't know they have a potentially harmful device fragment in their body, so they don't report it.”

Fischer's article offers tips for healthcare professionals to reduce UDF-related injuries.

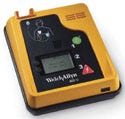

Welch Allyn Defibrillator Recall Is Class 1

|

The Welch Allyn AED 10 may cause failure in delivering therapy. |

Welch Allyn has recalled its AED 10 automatic external defibrillators manufactured between March 29 and August 9. An FDA notice in November designated the recall as Class 1.

The agency says there is a possibility that the recalled devices may experience failure or unacceptable delay in analyzing a patient's electrocardiogram, resulting in possible failure to deliver appropriate therapy. The notice says the possible failure or delay depends on the location of the defective part that stores an electrical charge on the circuit board. This comes after a Class 1 recall of the firm's AED 20 defibrillators was issued in October.

FDA Joins Warning on Cleaners

FDA and several other federal agencies have issued a public health notification to help avoid hazards associated with using cleaners and disinfectants on electronic medical equipment.

“Over the past two years,” the notification says, “the relevant federal agencies have learned about and collaborated to address problems associated with inappropriate use of liquids on electronic medical equipment. The problems included equipment fires and other damage, equipment malfunctions, and healthcare worker burns.”

The problems involved infusion pumps, ventilators, patient-controlled analgesia pumps, telemetry physiological signal receivers and transmitters, sequential-compression device pumps, infusion fluid warmers, and infant anti-abduction sensors.

Recommendations include:

Identifying equipment to which the notification applies.

Reviewing manufacturer cleaning and maintenance instructions and ensuring that all staff are trained to follow the instructions.

Protecting equipment from contamination whenever possible.

Taking additional specified precautions if there is a suspicion of equipment contamination with microorganisms that might pose a transmission risk.

Strictly adhering to all chemical manufacturer warnings, precautions, and cautions and following product directions for use.

Decontaminating equipment contaminated with blood or other potentially infectious material per OSHA regulations.

The notification says contaminated surfaces can include equipment in contact with blood or other potentially infectious material, surfaces touched by gloved hands after glove contact with patients, surfaces touched by patients, and surfaces contacted by or in the vicinity of aerosols and spatter. The notification lists 15 potentially contaminating substances, and also applies to surfaces whose state of cleanliness is uncertain.

FDA Issues IVD Draft Guidance

FDA has issued a draft guidance for industry and FDA staff titled In Vitro Diagnostic (IVD) Device Studies—Frequently Asked Questions, to assist manufacturers, sponsors, and others in developing IVD studies. It is particularly geared to those exempt from most of the requirements of the investigational device exemption (IDE) regulation. The guidance also provides a broad view of the regulatory framework pertaining to developing IVD devices.

FDA says the guidance information also is pertinent to investigators who participate in IVD studies and to institutional review boards that review and approve such studies. “The document is intended to facilitate the movement of new IVD technology from the investigational stage to the marketing stage,” it says.

Written in a question-and-answer format, the guidance provides a background and introduction and covers general regulatory issues, investigational studies, human subject protection, and data considerations.

The guidance also includes a glossary, references, and several appendices on the regulatory framework, sponsor and investigator responsibilities, and a suggested format for final reports. To access the guidance, visit www.fda.gov/OHRMS/DOCKETS/98fr/07d-0387-gdl0001.pdf.

Copyright ©2008 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like