Changes are sweeping European medical device regulations, and they will affect every company that markets devices in Europe. A 2007 amendment to the Medical Devices Directive (MDD) 93/42/EEC will come into force in March 2010. The bottom line of the amendment is that every medical device sold in Europe, regardless of its classification, must have a clinical evaluation (CE) report in its technical file. A CE report is a literature review that is submitted to the notified body to augment or substitute for new clinical data.

January 1, 2010

|

Photo by iSTOCKPHOTO |

How did such a game changer come about for the industry? In June 2002, a report by the European Commission’s Medical Device Experts Group (MDEG) concluded that most manufacturers didn’t possess adequate clinical evidence for their medical devices and that most notified bodies didn’t adequately verify the clinical evidence that was provided to them by manufacturers.1 The findings applied to Class I and Class IIa devices, as well as Class IIb and Class III devices.

In addition, the MDEG cited clinical evaluations as a major area of concern. The MDEG is composed of representatives from various organizations in Europe and each member state’s competent authority. The Clinical Evaluation Task Force, a subgroup of the MDEG, proposed the changes found in Directive 2007/47/EC that led to the amendments of MDD 93/42/EEC.2

Europe versus the United States: Direction of Literature Reviews

Both Europe and the United States require literature reviews in the course of conducting clinical trials and commercializing devices. However, Europeans and Americans have a fundamentally different view of their purpose. Europeans believe that a well-conducted literature review will point in a single direction such as:

?Whether a clinical trial is needed.

?Justification for the trial, if necessary.

?Whether the medical device is ready for commercialization.3

Americans, and FDA, come from a different perspective. The literature review serves specific purposes such as:

?To summarize the state of world knowledge through a report of prior

investigations.

?To establish that a device is substantially equivalent to another device on the market.

?To establish that a device can be used safely under the watchful eye of an

investigator.

?To establish that a device can be used safely in the day-to-day business of healthcare delivery.

The European view anticipates and demands an exhaustive review of the published (and unpublished) literature. For an old product like a wound dressing, this could consist of thousands of articles going back to the time of the ancient Greeks. However, for a familiar product like a tongue depressor, there may be only a limited amount of scientific literature available. The American view expects that a balanced and honest review will be conducted, but once the purpose of the review is fulfilled, the job is complete.

History of Regulatory Literature Reviews

|

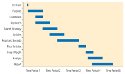

Figure 1. (click to enlarge) Timeline for a CE report. Depending on the company, it can take weeks, months, or years to create the report. However, the average preparation time is three to four months. |

Report of Prior Investigations. The first regulatory requirement for a literature review was circa 1980, when FDA brought forth the concept of a report of prior investigations, 21 CFR Part 812.20(b)(2). The report details prior investigations of the device, the purpose of which was to give the agency a history of device use. The report of priors is a requirement for significant-risk devices that require a full investigational device exemption, and the concept is useful, but not imperative, for clinical trials of nonsignificant-risk devices.4

MDD. Circa 1993, the Europeans raised the bar and said that a literature review constituted clinical evidence and could, in many cases, substitute for new clinical data. The MDD of 1993, Annex X, reads, “The adequacy of the clinical data must be based on either a compilation of the relevant scientific literature currently available on the intended purpose of the device and the techniques employed as well as, if appropriate, a written report containing a critical evaluation of this compilation, or....” This was new territory, because the regulators were overtly stating that retrospective data could adequately substitute for new, prospective clinical data. The provision may have arisen from a European aversion to clinical research.5

Clinical Investigation Plans. In 2003, ISO 14155-2:2003 further clarified the role of a literature review in clinical trials. Part 2 in 4.5.1 states,

The clinical investigation plan shall contain a critical review of the relevant scientific literature and/or unpublished data and reports together with a list of the literature reviewed. The conclusions from this review shall justify the design of the proposed investigation. The review shall be relevant to the intended purpose of the device to be investigated and the proposed method of use. It should also help in the identification of relevant end points and confounding factors that should be considered, and the choice and justification of control methods.6

Even further guidance was offered in Annex A of ISO 14155 Part 1, in which

performance of a literature review took on the aspects of the scientific method and was based on the groundbreaking work done by the Cochrane Collaboration.

It’s useful to remember that the ISO 14155 standards are adopted by the Committee for European Normalization and incorporated by reference into the directives. They therefore become de facto regulation in Europe, and the European device industry has a huge stake in how the standards are worded.

The Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF). In 2007, GHTF Study Group 5 published guidances on CE reports. They further emphasized the preference for using retrospective data in lieu of prospective clinical data with the statement, “Clinical evaluation of medical devices that are based on existing, well-established technologies and intended for an established use of the technology is most likely to rely on compliance with recognized standards and/or literature review and/or clinical experience of comparable devices.”7

Harmonizing European Union Directives with GHTF Guidances. An important policy that has slipped past most Americans is the European plan to harmonize the MDD and the European Commission’s Medical Device Guidance Documents (MEDEVs) with GHTF guidances. In an open statement issued by the notified bodies, it is “Europe’s intention to integrate GHTF guidance into the European legal framework to as full an extent as possible...[and] to replace the first part of the MEDEV on clinical evaluation with the GHTF document.”

This statement is significant because as Europe and GHTF become closer, the preference for retrospective data over prospective data for device commercialization is strengthened. Furthermore, it forces the hand of the ISO Technical Committee 194 WG4, the working group struggling to bring the 2008 ISO standard into the 21st century, to accommodate policies in the GHTF guidance and politicize the science of clinical research.

|

Table I. (click to enlarge) Example of article weighting or an appraisal of article suitability. |

Although fewer clinical trials are required in Europe, and devices come to market years and even decades sooner than in the United States, some European citizens feel that they are the guinea pigs of the Western world. In the spring of 2009, the European Medicines Agency made a play for taking over regulation of the device industry with backing from the European Commission. However, the move was succesfully blocked by the device industry, with the outcome that the industry has taken better control of its own regulation. One result is the requirement for new or updated CE reports for all medical devices sold in Europe.

CE Reports: A Three-Legged Stool. Think of a CE report as a three-legged stool. One leg is a report of any newly conducted clinical investigations of a device. Another leg is a report on unpublished data, such as biological safety data, bench testing data, or complaint and experience records. The final leg is a literature review of clinical investigations published on similar devices. For established devices, the literature review may serve as the primary source of clinical evidence to support commercialization and may justify not conducting new clinical investigations.

Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. The U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) has prepared an extensive document on reviewing the literature.8 First published in 2007 as a 128-page draft, this ongoing effort to write a comprehensive methods guide is periodically updated and is available for free from the AHRQ Web site or from the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. The AHRQ document is far more useful and complete, but it doesn’t have regulatory standing in the United States or Europe.

Databases. A note to Americans: it isn’t enough to search Medline. Even though this free, online database from the National Library of Medicine includes more than

19 million citations, dating back to 1948, about 2000 global medical journals aren’t included. To access medical journals, one needs to search Embase.

Embase, owned by Elsevier Publishing, can be accessed in at least three ways. The first is via subscription to embase.com, which provides access to both Embase and Medline citations through a Web-based front-end program. The embase.com site uses either full-featured Boolean logic or user-friendly check boxes for searches. Embase, without the inclusion of Medline, can also be accessed through subscriptions to Ovid or Dialog, which offer different front-end programs, and financial and service packages. To do a Europe-friendly literature search, access to Embase is necessary.

Methodology

|

Table II. (click to enlarge) Example of data weighting or the appraisal criteria for data contribution. |

One thing that Europeans and Americans agree on is how to do a scientifically sound literature review (see the sidebar “How to Do a Literature Review in 10 Easy Steps” on p. 78).

Duration and Timeline. CE reports vary in length from 30 to 300 pages. Two experts, who have written about 80 CE reports between them, indicate their past experience is that CE reports averaged about 30 to 40 pages for Class I and Class IIa devices. However, the British Standards Institute indicated that a 270-page technology assessment report from AHRQ represented the depth and breadth in which notified bodies would be looking in the future.9 See Figure 1 for an example of a CE report task timeline.

Article Weighting. Article weighting is the idea of assessing the data in one article as more valuable than data from another article (see Table I). The literature appraiser may choose to use other criteria or additional criteria. What matters is that the weighting criteria can be justified. For example, a comparison of risk factors might be useful.

Data Weighting. Data weighting focuses more on the quality and integrity of data (see Table II). For example, is the data from a well-controlled clinical study or from an observational registry study? Again, the appraiser may choose to use other criteria. For example, a comparison of biocompatibility data may be important.

Report Format. The CE report will have a predictable format and will include the following:

?Date of search.

?Name of the literature appraiser(s).

? Period covered by search.

? Purpose of the review.

? Description of the device.

? Intended use, indications for use, and claims.

? Selection criteria for literature articles, including sources of articles and reasons for rejection of articles.

? Keywords used for searching databases.

? Summary and grading of clinical data.

? Analysis of existing safety and complaint data, and new clinical data.

? Conclusions.

? Attached copy of search protocol.

? Attached curriculum vitae of appraisers.

? Attached full text copies of articles.

The Reviewer or Appraiser. The review should be conducted by suitably qualified individuals, who are called appraisers in Europe. The manufacturer must be able to justify the choice of the reviewer through reference to qualifications and documented experience. As a general rule, reviewers should understand the device technology and its application, research methodology for clinical investigations and biostatistics, and diagnosis and management of the device’s indications for use.

How to Do a Literature Review in 10 Easy Steps

Identify the purpose of the review.

Identify the article sources: i.e., Medline, Embase Google, abstracts or full articles, reviewed scientific literature, or unreviewed or unpublished data.

Decide on any filters or limitations: e.g., no articles before 1985, only articles on a well- defined topic or articles that relate to the device’s indication for use.

Gather the abstracts and list them in a table.

Read the abstracts; some may be excluded. Perhaps there are two articles about the same study. State the reason for exclusion in the table.

Read the remaining articles in full text and exclude the articles that are redundant, irrelevant, or unusable for other reasons, and state the reason for exclusion in the table.

Weigh each article according to relevant criteria.

Analyze the data with regard to the number of patients, success or failure of device, adverse events, etc.

Draw conclusions based on original purpose of the review.

Prepare a report.

Conclusion

With the new amendments coming into force in March 2010, notified bodies are marching their way through their product files, notifying manufacturers that a new or updated CE report is due on nearly every registered device. Manufacturers have waited until the last minute and are suddenly realizing that they may have a dozen reports all due within the next few months. Notified bodies are concerned, too. They don’t have the staff to review hundreds of reports within the space of a few weeks, and the amendments do not provide for a phase-in period. What will happen to devices that don’t have updated reports when the deadline arrives is yet to be decided.

References

1.MDEG, “Report on the Functioning of the Medical Devices Directive,” (London, The British Standards Institution, 5 June 2002); available from Internet: www.bsigroup.com/upload/Standards%20&%20Publications/Healthcare/MDDReport2002.pdf.

2. Directive 2007/47/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 September 2007 Amending Council Directive 90/385/EEC on the Approximation of the Laws of the Member States Relating to Active Implantable Medical Devices, Council Directive 93/42/EEC Concerning Medical Devices and Directive 98/8/EC Concerning the Placing of Biocidal Products on the Market, Official Journal (OJ) of the European Union, L 247/21, 21 September 2007; available from Internet: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/

LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2007:247:0021:0055:en:PDF.

3. G Bos, “Europe in Confusion, MDD Recast Delayed, ISO Declined,” Clinical Device Group, e-Conference, April 8, 2009; available from Internet: www.clinicaldevice.com/mall/

eConferenceCD.aspx.

4. Code of Federal Regulations, 21 CFR 812, Investigational Device Exemptions; available from Internet: www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfCFR/CFRSearch.cfm?CFRPart=812.

5. Council Directive 93/42/EEC of 14 June 1993 Concerning Medical Devices, OJ, L 169; available from Internet: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31993L0042:EN:NOT.

6. ISO 14155-2:2003, Clinical Investigation of Medical Devices for Human Subjects, Part 2: Clinical Investigation Plans, (Geneva: International Organization for Standardization, 2003); available from Internet: www.iso.org/iso/iso_catalogue/catalogue_tc/catalogue_detail.htm?csnumber=32217.

7. “SG5 Final Documents,” Global Harmonization Task Force, June 2007; available from Internet: http://ghtf.org/sg5/sg5-final.html.

8.”Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews,” (Rockville, MD, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], August 24, 2009); available from Internet: http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/index.cfm/search-for-guides-reviews-and-reports/

?pageaction=displayproduct&productID=318.

9. Negative Pressure Wound Therapy, Technology Assessment Report, (Rockville, MD, AHRQ, June 2009); available from Internet: www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ta/negpresswtd.

Nancy J. Stark is president of Clinical Device Group Inc. (Chicago).

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like