Manufacturers must prepare themselves with a thorough understanding of international nuances.

REIMBURSEMENT

|

Illustration by iSTOCKPHOTO |

As the world grows smaller, national politics increasingly affect global healthcare economics. Although the medical device industry has boosted its international harmonization efforts, wide variation still exists with respect to healthcare reimbursement. Therefore, device companies must understand reimbursement schemes in their relevant geographic markets before making any significant investment in product development.

The goal of this article is to provide foundational knowledge for U.S. device companies for selecting markets in which product reimbursement will most likely be secured. It also aims to help OEMs craft a unified approach to international product marketing that addresses differing national requirements, particularly in Canada and within the European Union (EU).

The Government's Role

There are many nuances in the reimbursement schemes of the United States, Canada, and the EU. A thorough understanding begins with examining the government's role in each scheme.

United States. Although the United States does not provide public healthcare to all of its citizens, the federal government does provide qualified healthcare subsidies through Medicare and Medicaid. CMS is the agency responsible for oversight of those subsidies. CMS makes coverage decisions that dictate what will be reimbursed by the government, making it both a regulator and a purchaser of medical devices.

Private insurers responsible for reimbursement to most patients are not bound by CMS coverage decisions, but do not typically deviate from them without cause. Private payers often cover items not yet addressed by CMS, such as orphan drugs or new devices. Private payers also adjust their reimbursement rates more quickly. But because there are myriad private insurers, presenting a device for approval can be costly. Therefore, favorable CMS coverage decisions are critical to device companies regardless of whether government reimbursement applies. FDA and CMS are separate government agencies but each influences the other. For example, CMS is unlikely to reimburse a medical device that has not been approved through FDA.

|

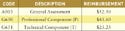

Table I. (click to enlarge) Reimbursement coding systems. |

According to CMS, healthcare insurers process more than 5 billion claims for payment each year. The agency uses standardized coding systems to help process these claims. Coding is used to translate the various care settings for medical device use into the language necessary for payment. The U.S. reimbursement scheme is based on the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) that CMS derives from broader systems provided by other organizations (see Table I). Manufacturers should know under which category they want their devices to be coded for greatest return before approaching FDA. If no 510(k) is possible, the manufacturer should make the strongest case possible for having its device fit into an existing code for similar devices. The alternative is creating a new code, which is time-consuming and more expensive.

CMS also considers several variables that FDA does not apply. The greater the patient need, the more likely it is that CMS would cover the device. It's important to note that FDA only validates the safety and efficacy, not the medical necessity, of the device. CMS views that necessity as reduced if other products are similarly effective, or if the magnitude of the potential benefit is otherwise diminished. CMS uses its Level II codes to cover those items not included in ICD-9. CMS has yet to adopt ICD-10, which lists many of the Level II procedures.

|

Table II. (click to enlarge) Canadian healthcare plans listed by province. |

Canada. Canada's healthcare system is based on universal publicly funded health insurance. The country uses a Beveridge system, which usually involves funding through taxation and payment distribution by the taxing government. The system is defined by the Canada Health Act (CHA). CHA provides for allocations of funds to Canada's provinces, each of which uses the money to set up healthcare payment systems for its citizens (see Table II).

|

Table III. (click to enlarge) Example health service codes and reimbursements. |

Provincial insurance systems established under CHA provide service-based reimbursement. Each province sets up a unique classification of services, and each service is given a code that corresponds to a payment amount that healthcare providers and patients can use to make individual decisions. Table III shows some examples. Definitions of each component are provided by the respective provincial system. Medical devices are reimbursed according to how the procedure and indication are coded. The coding is determined by each system based on approval information provided by Health Canada, the agency responsible for market approval. It is then up to the individual physician or hospital to determine whether reimbursement, and the profit margin created for performing a given procedure, justifies performance of that procedure.

Europe. Classification is the first step in determining how primary payers are reimbursed in the EU. But the EU's reimbursement landscape is difficult to navigate, mostly because the community is not fully harmonized. Influence from within the EU comes from the national Health Technology Assessment agencies of its member states, which are charged with promoting cost-effective technologies and eliminating harmful or ineffective interventions from the marketplace. The agencies are further organized into the European Network for Health Technology Assessment to facilitate information sharing and harmonization.

Because the EU treaty proviso stipulates that the community must respect the national rights of members regarding healthcare, there is tension between harmonization and respect for national rights. EU countries continue to offer tax-based public insurance at different rates based on individual government schemes.

The 27 EU member nations have independent control over pricing as well as different health payment systems. Almost all of the member countries have implemented evidence-based medicine, which requires medical device companies to demonstrate the safety and efficacy of each device prior to approval. In theory, all EU member states are equal, so achieving approval in one member state should provide access to other markets. In reality, however, each country's institutional arrangements for pricing, market access, and enforcement are different.

OEMs that want to sell their medical devices in Europe need to go through the same regulatory processes as non-OEM device companies in the region. The process starts with selecting a notified body of their choice—an organization that certifies devices for the EU based on national compliance assessments. Products in compliance are then identified by CE marking. Most countries have at least one or two fully independent notified bodies.

In addition, if an OEM chooses to outsource and intends to market and sell a medical device in Europe, it must take responsibility for the regulatory requirements and collect all of the appropriate documentation from the contract manufacturer for submittal to the proper agency.

The Role of Nonpublic Sources

The health payment systems of Europe and Canada are often considered national health systems with a single payer: the Ministry of Health. However, most of the countries have supplemental private insurance industries, and how each country operates in such a system varies widely. In the UK, for instance, about 80% of healthcare funding comes from general taxation, with 20% coming from other sources.1 The Italian National Health Service, by contrast, bears the cost of a declining percentage of total healthcare in Italy, with about 40% of payments now coming from nonpublic sources.2 In Canada, a robust private insurance market exists alongside public healthcare, with employers providing supplemental coverage for about 42% of all Canadian employees.1

In Europe, there are a number of payment sources for medical care in addition to public insurance. One major source is private healthcare insurance, but citizens may also establish third-party indemnity insurance with specific payment structures. Independent providers of benefits-in-kind also exist, allowing individuals to tailor policies to suit their needs.

There are other insurance entities in Europe that manage groups of providers, and these organizations offer reimbursement for services falling within the spectrum of provider expertise for the plan. This presents a challenge for a company trying to determine where to market a medical device in Europe, because each type of payer has different reimbursement schedules. For example, Luxembourg, France, and Belgium use the Bismarckian model. Under this model, payments are made by public insurance and third-party indemnity payers. Germany and The Netherlands also follow a Bismarckian approach, with third-party payers providing structured indemnity insurance as well as benefits-in-kind.

Global Strategy Development

It is critical to know whether payers will cover a new product and at what rate, so manufacturers must develop a reimbursement strategy very early. If the product is not covered, there is essentially no accessible market, because patients generally are not willing to absorb the high costs of devices and associated procedures personally. The most efficient way to approach global marketing of medical devices is to identify areas of commonality among international regulations and reimbursement criteria. Firms should bring products into conformity with those regulations and criteria and subsequently prioritize markets of interest and approach the applicable market nuances case by case.

Regulatory Classifications. Regulatory approval does not guarantee reimbursement. However, the classification of devices by the appropriate national agency is typically factored into reimbursement decisions by the applicable payers. In the United States, FDA classifications affect CMS coding and subsequent payments made for devices. Similarly, classification by Health Canada affects how products fit into provincial payment structures. In Europe, the challenge of guiding classification is exacerbated by multiple-agency participation.

Medical devices are classified by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an international organization including EU nations as well as countries outside of Europe, including the United States. But devices are also classified by national agencies. The UK utilizes a Medical Device Agency; France has the Health Care Product Safety Agency; and Germany has the Federal Institute of Medicinal Products and Medical Devices. The UK has also launched the National Institute of Clinical Excellence at the University of Birmingham to evaluate new and innovative technologies. In France and Germany, such national agencies not only review the clinical trials, but also set the prices, which affects the percentage of devices and procedures that are covered by the government or other payers.

Primary and Secondary Payer Effects. Negotiations in countries with public insurance are more political in nature than they are in the United States. Tax revenue determines the healthcare appropriations in each country. Residents of each country want the best possible public health insurance, but they also want to keep the highest possible percentage of their earned income. Therefore, tax payments and subsequent healthcare appropriations are ultimately dictated by prevailing view of the polity. In socialized countries, a device firm must determine whether the current trend is driving reimbursement to public or private insurance. It must look to the applicable government or insurance market practices to see how payment structures are determined and how payments can be negotiated.

Government-approved reimbursement often requires lengthy negotiations. For example, in France, if a device company's sales exceed the agreed-upon volume, the negotiation process is reopened and the product prices are further reduced.

In Spain, the government determines product prices, and reimbursement negotiations can take two to four years. Prices in Spain are based on innovativeness, profits, the amount of domestic research and development, volume and value of sales, manufacturing and marketing costs, and international price comparisons.

In Italy, products must first be registered, and then may be priced freely unless reimbursement is sought through the Italian National Health Service. Again, negotiations for reimbursement can be lengthy, and price is based on many factors, including a price comparison with at least four other European nations.

The UK boasts the fastest average time to market for medical devices following regulatory approval. It is probably the best place to begin marketing in Europe for companies located outside the EU. The government occasionally institutes across-the-board price cuts, but reimbursement prices are usually granted quickly.

Germany's Future Model. Germany is one of the leading high-tech countries of the EU. It converted to a diagnosis-related group (DRG) hospital care reimbursement system for medical device procedures fairly recently. Until 2000, Germany had a more traditional per diem reimbursement system; hospitals were reimbursed for long hospital stays to compensate for high-priced, innovative medical devices. Under the DRG system, however, the main push is to reduce the length of hospital stays, and all reimbursements are done via a catalog of diagnoses maintained by the German Health Technology Assessment (HTA) agency. If a device is not listed, the hospital may not be reimbursed if it chooses to use the new technology.

This new system has had an unexpected backlash for innovative medical devices. Unlike pharmaceuticals, which undergo extensive, long-term clinical trials, usually through a double-blind study, medical devices are often marketed after just two to four years of clinical trials. The number of patients involved in device clinical trials is much smaller, and it is often impossible for the patient and physician not to know a new medical device is being used.

In addition, some new medical devices are so superior to previous technologies that denying use of them seems unethical. HTA, which demands large clinical trials, double-blind randomized clinical results, and a number of high-quality published studies, often will not approve high-priced innovative medical devices, and thus the technology is not available within the approved catalog.

|

Over the next five years, Germany hopes to develop a reward system in which it provides incentives for high-risk devices to speed their introduction to the market. One incentive may be supplemental reimbursements. The country may also change the reimbursement rules at research hospitals, where expensive, innovative medical devices are usually first used. Overall, its plan is to further simplify the entire system, making it easier for hospitals to use new technologies. If Germany is successful, similar systems may emerge in other EU nations—a point of consideration for manufacturers of cutting-edge devices.

Conclusion

There is no solitary approach to ensure reimbursement for medical device technology internationally, but best practices should include centralized information management and guidance through the various national government and insurance schemes. OEMs should use this information to identify markets in which reimbursement will be most readily secured, or where it will be most likely to influence other markets, and start the reimbursement process there.

Scott Lloyd, Clarence Mayott III, PhD, Deborah Schenberger, PhD, Perry De Fazio, and Jerry Burke are analysts at Nerac Inc. (Tolland, CT). Contact them at [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]@nerac.com, [email protected], and [email protected], respectively.

References

1. C Jommi et al., “New Funding Arrangements in the Italian National Health Service,” International Journal of Health Planning Management 16 (2001): 347–368.

2. J Munn et al., “Single-Payer Health Care Systems: Roles and Responsibilities of the Public and Private Sectors,” Benefits Quarterly Q3 (2007): 7–16.

Copyright ©2008 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like