April 20, 2015

Microfluidics and smartphone-based applications mean SurModics' decades-old StabilCoat is stretching its legs in new ways.

Chris Newmarker

|

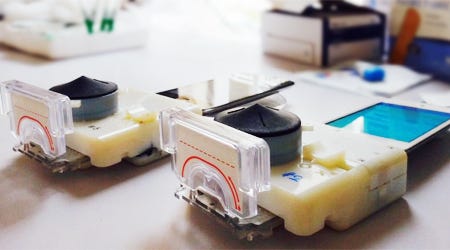

An inexpensive smartphone compatible device out of Columbia University could detect HIV and syphillis. SurModics' StabilCoat helped enable make Columbia's assays more durable and capable of withstanding high heat and humidity. |

Columbia University researchers did not have a run-of-the mill IVD device in mind when they approached SurModics early last year about using its StabilCoat for preserving proteins in immunoassays.

The Columbia device plugged into a smartphone and used a vacuum created by a compressed rubber bulb to move a single finger prick of blood through microchannels where various assays tested the blood for HIV and syphilis.

"They invented a brand new mousetrap," says Drew Pauly, director of in vitro diagnostics product development at the Eden Prairie, MN-based company. (Read a full Qmed story about the device here.)

Pauly, SurModics scientist Sean Lundquist and others at the company worked on and off with the Columbia researchers for about six months to ensure that the StabilCoat helped the proteins in immunoassays stand up to the hot and humid conditions of Rwanda, where the Columbia researches intended to test out the device.

The story provides a great example of how the shift to lab on a chip and other point-of-care IVD technologies are changing the game for companies in the diagnostics coatings business, where established IVD coating technologies are helping improve the performance of contemporary diagnostics.

The situation is resulting in a new chapter for StabilCoat, a decades-old coating made from a proprietary SurModics formulation that includes a bovine protein and other components. It is used to preserve proteins in an assay, and to block out other reactions with the blood that would cloud the results.

The coating helped the Columbia researchers create a lab on a chip that lives up to its name. "They're getting lab-quality results without the walls of a laboratory around them," Pauly said.

Lundquist says much of their time was spent helping the Columbia researchers figuring out the humidity levels and time period during which their manufacturing robots needed to apply the StabilCoat. Proper packaging to ensure the StabilCoat would last was also important.

"We tweaked some of the drying conditions. That was a big factor. And then there was also removing residual from channels. We worked with them on the best way to do that," Lundquist said.

"There's not an application note that you can find in the public domain for, 'How do I coat my microchannels?'" Pauly said. "As Sean indicated, it was giving them a starting place. 'Here's where we've typically started with building an assay. So here are some drying times. Here are some [humidity levels], some temperatures and durations for getting that to ... stay stabilized."

Such consultations are becoming increasingly commonplace for SurModics because a whole host of companies are seeking to get IVD out of laboratories and out into doctors' offices and other healthcare settings.

The standard for laboratory-based IVD has been polystyrene 96-well plates, Pauly says. "One well of that is a pretty big swimming pool for an assay to occur."

Now there are devices with microchannels with new geometries and tiny dimensions. "Surface energies change," Pauly says.

The situation means that channels could become clogged with proteins in certain situations, requiring other surface-modifying coatings.

Another challenge for Pauly, Lundquist and others at SurModics involves new materials: IVD device designers are also moving away from polystyrene and using moldable plastics such as cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) or polydimethylsiloxane PDMS that allow for more complex geometries.

The situation means there are plenty of puzzles for SurModics to figure out around use of StabilCoat these days. The overall goal is to make sure it continues to do what it has done so well for decades. "You're taking a biologic out of the body, a protein that doesn't like being outside of the environment. How do you keep it happy, active, available to do its job in the assay and detect disease? ... That's been the challenge for diagnostics since the earliest pregnancy assays," Pauly said.

Refresh your medical device industry knowledge at BIOMEDevice Boston, May 6-7, 2015. |

Chris Newmarker is senior editor of Qmed and MPMN. Follow him on Twitter at @newmarker.

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like