February 8, 2016

FDA's method for tracking medical device-related adverse events is so antiquated that it can take years for the agency to detect serious problems such as duodenoscope-related infections, reports the LA Times.

Qmed Staff

|

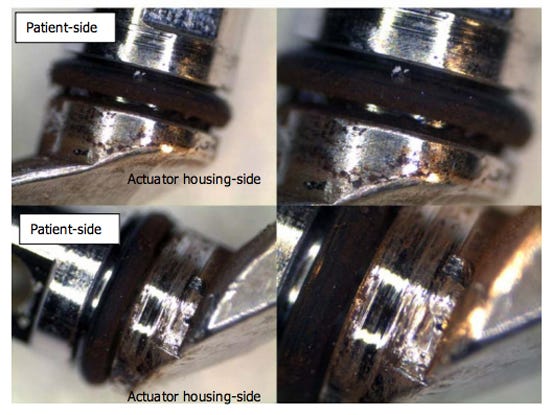

Pictures of a contaminated Olympus TJF-Q180V closed-channel duodenoscope. The O-ring shows signs of wear, and the actuator-side area is heavily covered with brown scale. (Image from the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee report) |

The FDA's system could have determined that some duodenoscopes have a high risk of infecting patients as early as late 2012--after an outbreak at a Pennsylvania hospital. But it wasn't until 2015 that the agency was able to determine the extent of the problem.

FDA didn't warn hospitals about the problem until the LA Times reported that duodenoscope-related infections killed three patients at a UCLA hospital.

Part of the delay was related to a series of missteps, including an FDA official who lost a crucial document, which came to light in a recent Senate inquiry. The DOJ is also investigating the matter.

The MAUDE database has also drawn criticism for being difficult to use. In addition, a number of hospitals and manufacturers are hesitant to report device-related problems because of the fear that doing so could be used in product-liability litigation. A Senate report released on January 13 revealed that none of 16 or more U.S. hospitals with duodenoscope-related infections had logged the incidents into the database, which is required when there is a medical device is linked to a death or injury.

Eventually, dozens of patients were infected by the scopes. It was also revealed that Olympus initially didn't have 510(k) clearance for theTJF-Q180V device that was implicated in some of the infections. FDA would later clear the device and explain in an FDA Web posting that it had chosen earlier not to pull the device from the market because doing so "could lead to an insufficient number of available duodenoscopes to meet the clinical demand in the United States of approximately 500,000 procedures per year."

Last last year, an FDA hearing related to the Essure birth control device revealed that the maker of the device, Bayer, had received more than 17,000 adverse-event reports related to the device. Only 5093 reports were listed in the MAUDE database as of June 2015.

A disclaimer on the MAUDE database website alerts users that the data may be "incomplete, inaccurate, untimely, unverified, or biased."

FDA is already working on improving the database. "The FDA is committed to establishing a national medical device evaluation system that leverages real-world evidence to help us more quickly identify safety signals," FDA spokesperson Deborah Kotz told the L.A. Times.

The Senate report also alleged that Olympus had underestimated the volume of endoscope-related infections while the Senate also concluded that Olympus had a history of blaming improper cleaning of the scopes as the cause of the infections.

But Olympus and another scope maker had sent five reports of scope-related infections to the FDA but only one of them was logged according to Senate investigation.

Olympus recently announced that it would be recalling and redesigning the device.

Other medical devices with poor track records of adverse events in recent years include metal-on-metal hip replacements, vaginal mesh used in surgeries and lead wires in heart defibrillators.

Retooling FDA's database for tracking medical device adverse events could take a decade, according to the LA Times.

"We need to build a better system to find these problems more quickly," Josh Rising, MD, director of healthcare programs at the Pew Charitable Trusts, told the LA Times.

The newspaper's investigation mirrors findings by released in January by the top Democrat on the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions Committee. The office of Sen. Patty Murray, D-WA, called for legislation to require and promote unique device identifiers (UDIs) in insurance claims, electronic health records, and device registries for faster FDA identification of problems.

"The failure of FDA's device surveillance system to rapidly identify and respond to duodenoscope-related superbug and antibiotic-resistant infections serves as just one example of the fallacy of a system that is primarily reliant on hospitals and device manufacturers to self-report information to FDA," the Senate report said.

Congress had passed legislation in 2007 that requires unique device identifiers.

Brian Buntz is the editor-in-chief of MPMN and Qmed. Follow him on Twitter at @brian_buntz.

Learn more about cutting-edge medical devices at MD&M West, February 9-11 at the Anaheim Convention Center in Anaheim, CA. |

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like