January 7, 2017

Scott Epstein shared how he took his structural hydrogel ureteral stent from concept to market without any government funding or strategic partnerships.

Amanda Pedersen

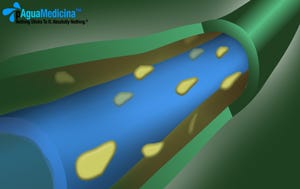

Based on a unique new material, Q Urological's ureteral stent has the potential to reduce hospital-aquired infections.

When Scott Epstein tells people about his medical device business in the Boston area and the technology he has developed, they often assume he is a product of Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). An MIT background would make sense, given his mechanical aptitude and geographical proximity to the university.

But Epstein, founder of Natick, MA-based Boston Scott Corp., and its subsidiary Q Urological Corp., did not go to MIT, and would be quick to challenge anybody's assumption that his non-MIT status matters.

In fact, a 33-minute conversation revealed many quirks that set Epstein apart from the typical medical device entrepreneur crowd.

Just A Guy With An Idea

Through what he describes as "unusual and unfortunate circumstances," Epstein built his company from the ground up without any financial support from strategic partners or government organizations.

In many ways, he is the proverbial starving artist and, in his own words, "a classic poster-child of dyslexia," surrounded by business rock stars who probably didn't always understand his methods or see the long-term value in his work. Not that it would have deterred him any.

Simply put, Epstein told Qmed, he's "somebody who had an idea."

He was the 12-year-old kid who would take apart the lawn mower just to figure out how it worked and see if he could put it back together again.

And yet, after more than a decade of working through the research and development phase to design a hydrogel pediatric ureteral stent - not a stent with a hydrogel coating, but a 100% structural hydrogel stent - Epstein's company just received its second FDA 510(k) clearance and is getting ready to bring the innovation to market.

How Did He Do It?

All of this begs the question, what was his secret to success?

"I just wanted to do this. I had a passion and I was willing to sacrifice," Epstein said. "I have a focus and I enjoy it. That's the reward."

So he bought a modest facility roughly 15 years ago. "It was the place I went where I tinkered, where I developed a technology, and where I invented a manufacturing process that could produce that technology."

The upside to bringing a medical device to market without a venture partner or institutional funding, Epstein said, is that he doesn't owe anybody anything to speak of and he isn't forced to have an exit strategy or answer to investors. He has an advantage that many venture-backed CEOs only wish they have: he gets to call his own shots.

And at the end of the day, Epstein isn't driven by the bottom line. "If I only make $1 next year, over my overhead, I'll be laughing all the way to the bank," he said.

Epstein has come to understand the importance of risk taking. Most of the time, he said, he already knew the answer -- he just had to figure out how to get to it. He's also learned to embrace failure as part of the process.

"Failure is part of the fuel that gets you to the answer," he said.

The Fruit Of His Labor

So what did all of that work and sacrifice result in? The development of a structural hydrogel platform technology, called pAguaMedicina, that has the potential to diminish biofilms on medical devices. And that could translate into a significant value proposition, considering the industry's ongoing battle with hospital aquired infections and superbugs.

Eventually, Epstein's goal is to leverage the technology for a broad range of vascular, urological, and gastrointestinal applications.

As a raw material, his structural hydrogel is similar to human tissue. "Nothing sticks to it," he said. "Absolutely nothing."

Contrary to what many might assume, the technology is not a hydrogel coating, but rather a soft, compliant material that constitutes the device itself.

How Does It Stack Up?

The ureteral stent is similar to predicate devices in terms of delivery and retrieval, but incorporates a differentially larger end, as opposed to the common pigtail design, that helps the device maintain position in the renal collection junction, according to Q Urological.

It's also designed in such a way that it does not distort or buckle, and in terms of mechanical strength the device compares well to conventional stents, without requiring a scaffold, Epstein said.

The stent can be removed using a grasper, the company noted, however the stent will stretch, which is integral to the force required to dislodge the device from the upper urinary collection system.

Infection control potential

"The diminished likelihood of biofilms means less bacteria and infection," he said, although there is much work still to be done to prove that claim in a clinical setting.

Beyond that, however, is the potential vascular applications of the technology, which is ultimately where Epstein wants to go with the platform. In animal testing, he said, the material showed no indications of blood clotting, even in small arteries.

Using the structural hydrogel as a raw material for vascular access and repair could potentially diminish many of the quality of life issues and related healthcare costs, he said.

Amanda Pedersen is Qmed's news editor. Reach her at [email protected].

[Image credit: Q Urological]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like