Wearable health technologies are in heavy demand but these three considerations must be incorporated when developing connected medical devices.

January 26, 2016

Wearable health technologies are in heavy demand but these three considerations must be incorporated when developing connected medical devices.

Bill Betten

Much attention has been paid to wearable technology, ranging from watches, pendants, or clip-ons. This past holiday season Fitbit's app was no. 1 in downloads on Apple's app store, a strong indicator of sales of the hardware. For the 3rd quarter of 2015, Fitbit sold 4.8 million devices according to RBC Capital Markets, holding a 22% market share. Misfit Wearables, a maker of wearable activity trackers, was recently acquired by Fossil Group, a watch manufacturer, for $260 million, further demonstrating the interest in this space.

However, Fitbit is now facing a class action lawsuit over the accuracy of the devices, particularly for monitoring heart rate, one of medicine's "vital signs." While the rapid growth in sales of devices for health and wellness has occurred, this has overwhelmingly been in the consumer sector, not in the regulated medical device space.

Here are the key considerations to keep in mind when developing connected medical devices.

Regulatory

One of the key differentiators between a useful medical device and a consumer device is that the former is under the purview of the FDA in the U.S.. The recent proliferation of wearable devices clearly approaches the regulatory boundary, depending upon what the companies selling the devices have to say about the intended use of the device. Guidance by the FDA in 2015 indicated the agency won't vigorously regulate devices as long as they're not harmful and generally encourage healthy habits, which covers most of the consumer devices available today. The few FDA-cleared wearable (or at least portable) devices today tend to be focused devices such as cardiac monitors and blood glucose measuring devices that enable clinical action or help in clinical decision making of some sort.

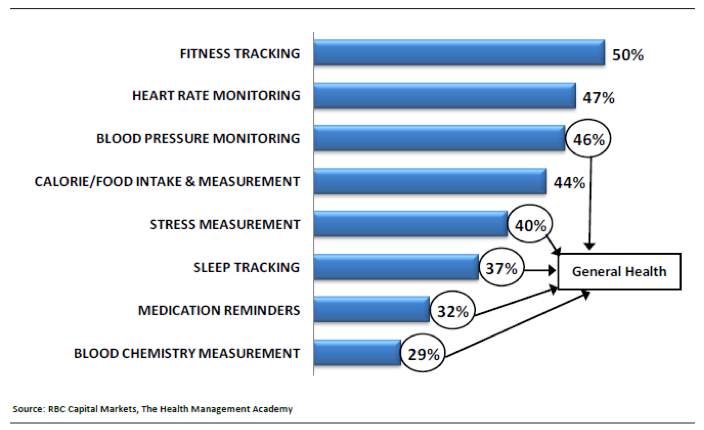

The RBC Capital Markets Consumer Health & Information Technology Survey recently surveyed 1500 healthcare consumers regarding their interest in use of wearable technology with the results noted below. As users focus on potential applications beyond health and wellness, the specter of regulatory approval, with the attendant consequences, becomes a challenge.

Survey interest in wearable technology measurements

Testing

To be useful for medical purposes, the accuracy and efficacy of each device must be measured. This brings us to a second consideration, validation of the device. Realistic expectations about the use of the devices must be set by the manufacturer and made clear to the user. Medical device manufacturers routinely address the performance issues associated with the claims for their devices, including clinical trials if appropriate.

Depending upon the particular claims being made and whether or not previous devices have existed, the level of required testing is determined. Clinical trials focus on demonstrating both safety and efficacy. Even if the device does no harm and is deemed safe to use, this does not mean that the device actually does what is intended. So, clinical trials are intended to demonstrate that the device does what the company claims for it within the generally accepted accuracy and tolerances associated with the condition being monitored.

For example, while wrist-worn devices are popular due to their conventional form factor, it is difficult to extract meaningful medical results from that location due to motion artifacts due to the physiology of the wrist, skin variations, and even the mechanical fit to the wrist. This explains why these devices have largely been constrained to the consumer space. To be sold as a medically regulated device, these constraints would have to be addressed through testing over the various combinations and limits of conditions, a process that can be long, complex, and costly.

Standards and Interoperability

That isn't to say that some combination of medically relevant devices and consumer wellness devices can't be useful. That leads to a third area of consideration -- interoperability. Interoperability can be defined as the ability of a product to work with other products without special effort on the part of the customer. Two approaches commonly exist to enable interoperability: adhering to published interface standards; or making use of a "broker" of services that converts one product's data into that of another.

For instance, an activity monitor, while not providing clinically relevant information on its own, can be used in conjunction with a heart rate monitor or pulse oximeter to provide insight into why the heart rate might be elevated or the oxygen level low. However, in order for that fusion of information to happen, the devices must communicate.

While standards exist, even within the medical community adoption can be slow and isolated. In the 1990s, medical imaging evolved from isolated film rooms to a networked ability to send images around the world through the definition of the DICOM standard and the advances in technology associated with networks and displays.

Today images can even be displayed on portable devices such as a cell phone, when used with an approved application. The Continua organization has worked to establish interoperability of devices such as pulse oximeters, weight scales, blood pressure meters, and other, using consumer-oriented communication technologies such as Bluetooth LE (low energy), enabling the spread of relatively inexpensive systems that can be used for monitoring of the elderly or chronically ill.

HL7 exists for the exchange and integration of electronic health information. Within their respective domains, these activities continue to drive interoperability within the medical space. However, after decades of work, it still results in islands of information that don't quite communicate. Adding the many consumer devices to this mix will only further complicate the fusion of information into the promised Big Data.

Soren, a Swiss research firm, projects that the wearables market could exceed $40 billion in the health care market alone. How that dollar amount translates into wearable technologies, whether wrist-worn, discrete elements, woven into clothing, or perhaps even embedded into our bodies will prove to be an interesting journey. Whether the bulk of that money is spent on consumer or medical devices will be determined in part by addressing these design considerations, and by building products that deliver additional value to the user.

[Photo Credit: iStockphoto.com user blackzheep]

Bill Betten is director of business solutions at Devicix, a medical device design and product development firm.

You May Also Like