September 16, 2016

As medical devices get smaller, valves are evolving to suit OEMs' needs.

Frank Vinluan

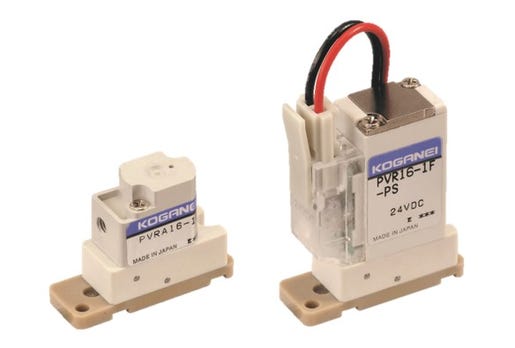

This Koganei PVR media isolation valve has less than 35 mL

of dead space, which is important for ensuring accuracy and

repeatability in laboratory and testing equipment.

As medical devices get smaller and more mobile, medical device manufacturers continue to look for valves that are smaller yet also have high flow capacity. Meanwhile, they also want valves to consume as little power as possible. Those requirements are familiar to valves suppliers. But as medical technology increasingly finds a place by a patient's bedside, The Lee Co. (Westbrook, CT) is also seeing an additional requirement: valves that are quiet.

[See The Lee Co. (Booth #633) at BIOMEDevice San Jose, December 7-8, 2016]

"If you have an instrument that's next to your bed, you really don't want to hear clicking sounds in your instrument," explained Christopher Marchant, Lee's marketing manager.

|

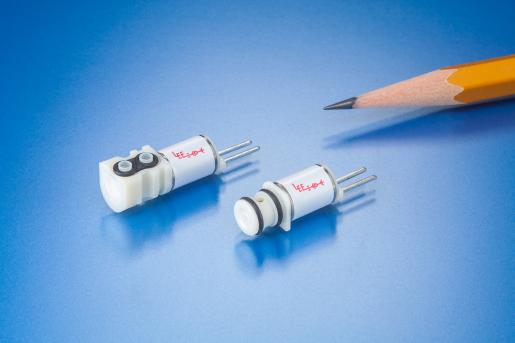

The Lee Co. makes this two-port high-density interface (HDI) solenoid valve for miniature fluidics applications in a smaller footprint. |

Valve technology is evolving in step with miniaturization trends in medical devices, an evolution that comes with growing pains. Space in medical devices is limited, but there are also limits to valve technology. Valves can only become so small before they bump up against the laws of physics, Marchant said.

Koganei Corp. (Tokyo, Japan) also sees OEM requests for valves that are smaller and more energy efficient.

[See Koganei Corp. (Booth #316) at BIOMEDevice San Jose, December 7-8, 2016]

In media isolation valves, which are used in testing or diagnostic equipment that call for high purity or the capability of isolating media, the company aims to reduce the dead space of air created when fluid flows through these types of valves. Reducing this dead volume is important for improving the accuracy and repeatability of laboratory testing equipment, explained William Miller, a U.S.-based sales manager for Koganei. Air in this dead space is one of the variables OEMs want to address to improve how a device or diagnostic instrument performs.

"Purity has to be the key component," Miller said. "You can't have many different variables of contamination."

Both Lee and Koganei supply valves for several different industries, but industrial applications don't overlap much with medical device valves, Miller said. Automotive companies, for example, focus on low prices. But medical device requirements for valves are more nuanced and complex. Medical OEMs ask questions about valves that are just not asked in the manufacturing sector, Miller added.

But Lee has found some instances in which valve technology in non-medical applications is useful in medical products. For example, the company supplies high-speed dispensing valves that handle fluid quantities as small as nanoliters. That capability, adapted from inkjet printing, proved useful for medical and scientific applications that require high accuracy and precision, Marchant said.

Regardless of the application, medical device makers are asking suppliers if they can eek out more life from their valves. Ideally, a valve's life expectancy matches the life expectancy of the device, Marchant said. But over hundreds of millions of cycles, valves can leak, compromising the life span of the component and the device. One way to increase a valve's life span is to use alternate materials that can provide a good seal that minimizes leakage.

Lee monitors the market to see what medical OEMs need from valve suppliers. If the OEM wants to move forward on a particular project, Lee engineers can work with the OEM on design concepts and provide samples. Lee provides both stock and custom valves. In many cases, a stock valve is a starting point for discussing whether a custom solution is needed.

Though Koganei was founded in 1934, the company is a relative newcomer to the United States. In 2015, the company decided to expand from Japan into North and South America, operating from a U.S. headquarters in Fremont, CA. Koganei is different than some other valves companies in that it sells products in the United States and Canada only through distributors. Those distributors tell Koganei which products or requirements medical OEMs are asking for. But that doesn't mean that Koganei doesn't work directly with medical device makers.

Working from a stock valve, an OEM may ask Koganei about adjusting a valve's power consumption or its flow rate. Sometimes those comments represent broad feedback about valves in devices, Miller said. But in other cases, a medical OEM is considering a product that would be proprietary to the OEM. If it's the latter rather than the former, Koganei and the OEM need to quickly clarify exactly what the device maker needs, Miller said. For example, if a device maker asks for valves that can handle liquid nitrogen, Koganei would decline that request because the supplier does not make on valves that operate under extreme cold. When a device's requirements go beyond what Koganei offers, the company suggests others with that expertise rather than proceed with a custom valve, Miller said.

For Koganei, the typical sales cycle from the first meeting to prototyping and testing typically lasts 16 to 18 months. In that period, Koganei tries to understand as much as possible about the application in order to determine the best valve solution. Koganei will ask what media would be passed through the valve, as well as its temperature. That information helps the company determine what type of seal materials would be appropriate for the application. Koganei also needs to know what kind of duty cycle the OEM expects from the valve, whether it's 5 million cycles or 10 million cycles. Valve suppliers also need to know how a device will be assembled. For example, an OEM's plan to assemble the device in a Class 3 cleanroom may not modify a Koganei valve, but it could require the company to manufacture the valve differently than how it is currently made.

It's important for medical device OEMs to convey clearly the exact problems that they are trying to solve, Marchant said. Understanding that problem can help a supplier find the valve solution. But sometimes, information does not flow freely. Even with non-disclosure agreements, some OEMs don't pass along key details about their devices. Marchant understands that there are proprietary aspects of devices that medical OEMs don't want to disclose. But he said that sometimes the valve supplier needs to know more, such as what is feeding the valve or how the valve will interact with other components in the device.

"Not having that information minimizes how much support we can give them," he said.

Frank Vinluan is a contributor to MD+DI. Reach him at [email protected].

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like