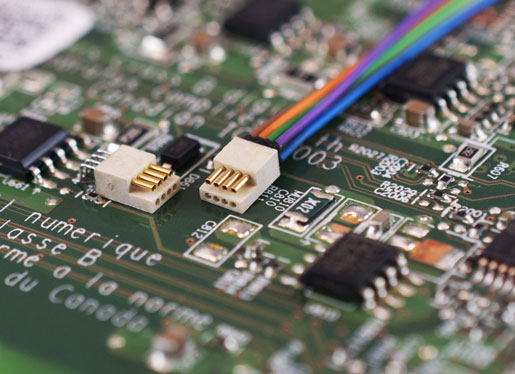

Electronic connectors come in a variety of forms to best fit the size, shape, and intended use of each medical device.

July 31, 2015

Frank Vinluan

Nano-sized connectors can be made in a rectangular shape to match the leads on a printed circuit board.

Electronic connectors are ubiquitous in medical devices, connecting one device to another in order to carry data, signal, and power. The most commonly found medical device connector is a front panel connector that plugs into machines moved around the hospital on carts. While these large, standard connectors aren’t going away any time soon, medical device manufacturers continue to develop products in smaller and more portable form factors. The progressively smaller footprint of medical devices is challenging suppliers to make connectors smaller without sacrificing functionality.

“Combining the electrical and the cable performance in the connector is a challenge we’re facing as we’re going into smaller [form factors] and higher speeds,” explains Bob Stanton, director of technology at Minneapolis-based Omnetics Connector Corp. “It’s not just the shape and the mechanics. It’s the performance.”

As medical devices become smaller, the electronics within them change accordingly. Computer chips can do more than ever, but they also draw less power. In a connector, the pins need to be a certain distance apart in order to carry voltage, Stanton explains. Smaller devices require less voltage, which means that the pin distance in the connector can also shrink, allowing for a smaller connector. Smaller devices call for microconnectors, or the even smaller nanoconnectors.

When it comes to choosing electronic connectors, medical device designers should consider both size and shape, as well as the application of the device. For example, a designer would choose a circular connector over a rectangular one in order to match the round cable and keep the device small, Stanton says. When a device is designed to enter the body, designers need a connector no bigger in diameter than the device. As an example, Stanton points to transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT), used to treat an enlarged prostate. TUMT destroys excess prostate tissue with a small microwave antenna inserted through the urethra.

“You don’t want [the connector] any bigger in diameter than the wire has to be,” Stanton says. “A nanocircular [connector] lets you fit in very small places and be the same shape of the sensor, or the camera, or whatever it is.”

|

Micro-size connectors with a hybrid pin configuration can carry power, plus a mix of smaller signal wires. |

But rectangular connectors have their place, too. A design engineer might want a rectangular connector because all of the leads on the printed circuit board are rectangular, Stanton explains. A direct neural interface, which connects to the spinal nerves or the brain, has a circuit board about the size and shape of a postage stamp. A rectangular connector fits the shape of the board.

Designers can choose from a number of different types of connectors depending on need and turnaround time. Off-the-shelf, also called standard connectors, are products routinely kept in stock because they are the connectors used and ordered most often, says Randy Jew, applications engineer for Rohnert Park, CA-based Lemo USA. These connectors can be found at the best prices and ordered with the shortest lead times.

“Generally, when an OEM is designing a device that will have low annual quantities of about 500 or less, they choose a standard model connector,” Jew explains. “If they have quantities greater than 2000 a year, they can begin to consider customs or hybrids.”

A hybrid connector contains two sizes of pins in the same connector: one size to carry power and the other to transmit signal. Hybrid connectors allow designers to develop a product that does not require two separate wires and two separate connectors for power and signal. Robotics, prosthetics, and medical devices that call for moving or articulating something would typically use hybrid connectors, Stanton says. Hybrid connectors are also found in the laser devices used to remove skin wrinkles. These devices handle multiple signals for the laser, the sensors that detect temperature, and sensors for the cooling system accompanying the unit.

As medical devices become more sophisticated, designers may opt for a custom connector. A custom connector is made to fit exactly what the designer is looking for and will perform to specifications, Jew says. But custom connectors are also more expensive and will have longer lead times, at least at first. Custom connectors require additional time to design, prototype, and then bring into production. In certain circumstances, a custom connector might also be chosen in order to meet a required level of medical cleanliness.

Increasingly, designers are looking for the connector to have a particular fit with the size or appearance of the device, giving it a sleek look, Stanton says. Cochlear implants, for example, employ custom connectors that are small, flat, and thin.

Not all connectors are made for the long haul. Devices that come in contact with the skin or blood may have single-use attachments that employ disposable connectors. Neonatal monitors, for example, now routinely use sterile, single-use attachments with disposable connectors. When the device needs to be used again, a sterile connector can be plugged into the instrument for the next patient.

Designers can make mistakes in choosing connectors, such as making connector contacts that are too small for the current contact or choosing the wrong material for the application, Jew says. Designers can also choose the wrong cable materials for the application. Stanton says he sees problems arise when designers aim for the lowest cost option. Materials vary in quality and durability, and designers can make the appropriate choice by considering the number of cycles a connector is certified for, as well as the longevity of the device. Designers can also avoid problems by leaving sufficient lead time to work with the connector company, Stanton says.

“A little more front-end investment will give them a pretty good product at a reasonable price, but it won’t be the cheapest,” he says. “The cost will come down in time.”

Learn about the latest medical device technologies at the MEDevice San Diego conference and exposition, September 1–2, 2015. |

Frank Vinluan is a contributor to MD+DI. Contact him at [email protected]

[Images courtesy of OMNETICS]

You May Also Like