Cardiovascular

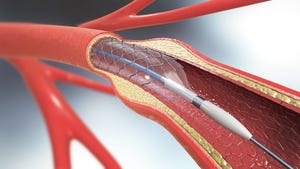

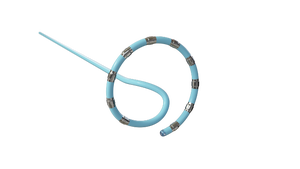

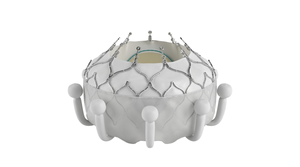

FDA approved Boston Scientific's Farapulse system in January for pulsed field ablation treatment of atrial fibrillation.

Cardiovascular

Boston Scientific's Farapulse Is a ShowstopperBoston Scientific's Farapulse Is a Showstopper

Electrophysiologists are giving the new pulsed field ablation system a warm welcome.

Sign up for the QMED & MD+DI Daily newsletter.

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

.png?width=300&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)