October 2, 2015

With U.S. medical device executives facing prison time over their marketing, a constitutional challenge is being mounted against FDA's powers.

Qmed Staff

|

Patrick Fabian (left) and William Facteau were executives at Acclarent. |

It is very possible that William Facteau and Patrick Fabian are facing prison time for doing something that a lot of their medtech executive peers did: finding creative ways to market medical medical devices for uses not specifically cleared by FDA. The two are claiming that their actions were supported by the First Amendment.

If anything, they have been accused of being too obvious about it while running Acclarent, a sinus-balloon company that Johnson & Johnson acquired for $785 million in 2010. And they managed to be so blatant about it right at the same time that federal prosecutors were deciding that merely fining companies for such transgressions wasn't enough; company executives can now be held personally liable.

The result is a scrappy fraud case in federal court in Massachusetts that has been recast as a free-speech case by the defendants. Fabian and Facteau have been charged with 18 counts including conspiracy, securities fraud, wire fraud, and introducing adulterated or misbranded medical devices into interstate commerce.

The case could call into question FDA's say over a device's intended use. The executives' attorneys claim that Facteau's and Fabian's promotion of an Acclarent device is supported by their right to free speech. They are therefore arguing that the grand jury in the case was misinformed, which they say would warrant a dismissal. If that happened, a new grand jury would then be instructed to meet and the original evidence--spanning six million pages' worth of documents--would be reintroduced.

With medical device and pharmaceutical executives such as Facteau and Fabian facing the possibility of eating prison food over their companies' marketing, the argument that they have a First Amendment right to say what they want about their products--as long as they can somehow argue that their claims are backed by evidence--is gaining strength in the courts.

"The freedom of speech argument has been used a lot in the drug world," says Michael Drues, PhD, president of Vascular Sciences (Boston). "The argument can be justified in some cases and it is starting to be applied to medical devices as well."

A big question to consider is what role FDA, medtech companies, and physicians each have in determining how a medical device is used.

Cost of Doing Business

In a way, getting fined for marketing off-label uses has become a cost of doing business for medical device companies.

For years, some medical device companies have seemed to subscribe to the notion that it is better to ask for forgiveness than permission when it comes to regulatory affairs. "One possibility is that they decided to promote a device for an indication they knew wasn't supported by their FDA clearance, but decided to do it anyway because it is a business decision. Some medical device companies concluded that the likelihood of getting smacked isn't very high and if they lose, the fine may pale in comparison to the market opportunity," Drues says.

|

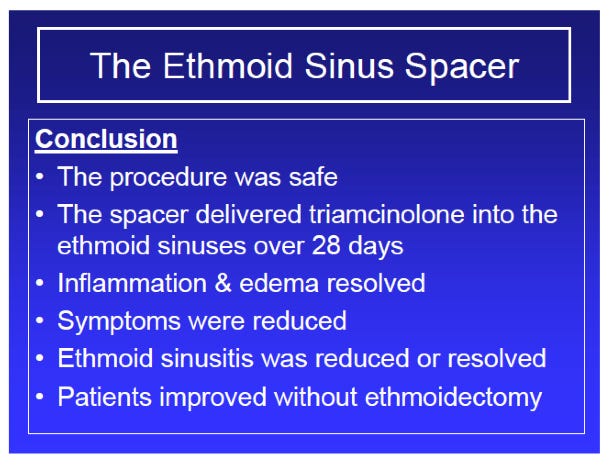

An internal Power Point slide from Acclarent discusses the product's use to deliver the drug triamcinolone to the sinuses in a clinical study performed by Frederick A. Kuhn, MD; Howard L. Levine, MD; Christopher T. Melroy, MD; and Andrew J. Diamond, MD. |

"A lot of times, companies will massage the language in regulatory documents so FDA regulators understand one thing and doctors understand another," Drues says. The simple reality is this: whether you are talking about a medical device, drug, or combination device product, we can put anything that we want on the label that FDA agrees to. Once the product leaves our door, we have no control over how it is used."

The notion of a device's intended use can sometimes be ambivalent, which can make it difficult for a medical device company to know what to say when marketing a device, according to Drues. "It's almost like a two-year old trying to feel out what his or her boundaries are before he or she gets smacked. In my opinion, there is too much interest on what is said and not enough on what happens in the real world."

Next Chapter:

Creative or Fraudulent? How Acclarent Made Sinus Balloon Tech Worth $785M

Learn more about cutting-edge medical devices at MD&M Philadelphia, October 7-8. |

Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our daily e-newsletter.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like