Compliance Is Not Enough: The Benefits of Advanced Quality Systems Practices

Originally Published MDDI May 2004

May 1, 2004

Originally Published MDDI May 2004

Quality

A recent survey suggests that basing quality strategies on more than just regulatory compliance offers not only additional benefits, but actually improves compliance.

Jennifer Parkhurst and Beth Shaw

The need for regulatory compliance in the medical device industry is a given. But is focusing strictly on compliance the best way to achieve it? Or is it better assured through a comprehensive and dedicated quality strategy? These were among the questions addressed in a recent survey of MD&DI readers.

The results indicate that those companies with the best performance in FDA inspections are the ones whose quality practices go beyond merely complying with regulations. These outstanding companies embrace a number of critical principles. First, they believe that quality leadership is essential. For them, quality efforts can fully succeed only if corporate management makes it a top priority. But in addition, in these companies, every employee is responsible for quality—not just the quality assurance department. Recognizing the importance of suppliers and partners, these companies also attest to the importance of having their partners actively engaged in their quality efforts. And to help elevate all quality processes in the company, they also make strategic use of information technology.

|

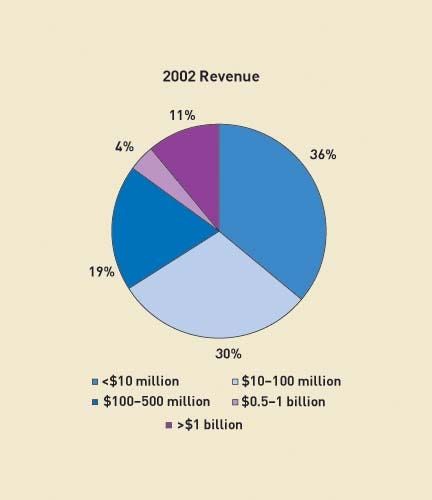

Figure 1. Respondent companies' 2002 revenues (click to enlarge). |

Conducted in September 2003, the survey was sponsored by MD&DI and Pittiglio Rabin Todd & McGrath (PRTM). The goal was to collect information on baseline quality practices of companies that strive to achieve and maintain compliance, processes that help companies improve quality performance, and practices that go beyond the regulations to establish a true culture of quality. The survey results reflect the participation of more than 300 individuals, representing 260 FDA-

regulated medical device companies.

Survey participants represent a broad cross section of the medical device and equipment industry, as demonstrated in Figures 1–3. More than 80% are established commercial organizations; the rest are start-up and precommercial companies. Some 64% represent companies that generate more than $10 million in annual revenues; more than 10% represent companies that generate more than $1 billion in annual sales. Many also make a variety of Class I, II, and III devices. In addition, 45% of respondents are members of senior management (director level and above). Roughly half work in quality or a quality-related function, such as regulation.

|

Figure 2. Commercial companies represent the majority of survey participants (click to enlarge). |

About 43% of survey takers said that they had at least one FDA inspection during the last two years. Of those, slightly more than half said that no significant findings resulted. We defined this group as advanced performers. Compared with the rest of the population, these companies reported distinctly different management practices that led to better quality and overall business operations. We subsequently talked with several of these companies (as well as some with audit findings) to learn more about their practices.

The survey was organized into four main areas: management oversight and reviews; performance measurement; quality policies and procedures; and systems, information, and tools. We analyzed the survey results for each area, and contrasted the key baseline practices common to most survey participants with the practices of the advanced performers. We could then provide insight into the inner workings and culture of those organizations with a proven track record on quality.

Management Oversight and Review

|

Figure 3. Types of devices manufactured by participating companies (click to enlarge). |

Almost all survey takers agreed that quality is a key part of their corporate strategy and goals. But not all believed their companies fully backed this up with resources. In terms of regulatory compliance, many felt that their companies allocate sufficient resources. But in terms of raising quality improvement efforts beyond compliance, fewer than 60% felt that their companies devoted enough resources. By contrast, almost all advanced performers reported that they give adequate resources to staffing quality compliance initiatives, and more often allocated adequate resources to quality improvement initiatives as well.

FDA's quality system regulation (21 CFR Part 820) is essential to regulatory compliance. But does it help foster innovative quality practices? Survey takers were split on this question (See Figure 4). Just 14% felt that the regulations spur innovation. About one-third said the regulations provide the right amount of guidance in assisting companies to design and develop their quality systems. However, more than 40% said the regulations are helpful but difficult to translate into practice. A handful said that the regulations were confusing and outdated. Regardless of their views on the regulations, the advanced performers go beyond regulations and use their corporate emphasis on quality as the most common driver of their system overall.

|

Figure 4. The majority of respondents find the current QSRs helpful, but difficult to implement in their companies (click to enlarge). |

The frequency of management reviews varied among survey takers. As shown in Figure 5, more than 70% reported holding management reviews at least every quarter with the senior management team. Annual management reviews were next, at 22%. The review meetings generally include people from a broad cross section of job functions; more than two-thirds of respondents include staff from quality, manufacturing, regulatory, and R&D. Three-fourths of respondents include middle and senior management in the meetings.

A majority agreed that their management reviews have a clearly defined purpose. Just 2% of respondents reported not having a clear purpose for management reviews; all respondents in this group reported audit findings in the last two years.

Approximately 75% of survey takers indicated that review of past quality performance is the primary objective of their management reviews. This is evident in the top four metrics reviewed by the overall survey population: customer complaint data, internal audit results, nonconformance data, and corrective and preventive action. Only one of these metrics, internal audit results, is primarily forward looking (because the problems found have often not resulted in product problems).

|

Figure 5. More than 70% of survey |

As shown in Table I, advanced performers put somewhat more emphasis on proactive metrics.

Advanced performers also work with their partners—meeting regularly and monitoring their performance. This is a significant priority in their management oversight responsibilities. For emerging medical device and equipment companies, as well as for contract manufacturers, this is especially true. “Our corporate business model is based primarily on partnerships,” said Truc Le, senior vice president of operations, quality assurance, and regulatory affairs at Nektar Therapeutics (San Carlos, CA). “We consider working with partners a critical component of our strategy and management responsibility.”

Management's leadership in quality reviews is central to the process. The organization as a whole takes its cue from the senior management team. If management takes quality seriously, the rest of the organization tends to follow suit. For such companies, quality becomes an integral part of the culture.

Performance Measurement

|

Table I. Advanced performers tend to emphasize proactive metrics more than |

The majority of survey takers use quality metrics as part of the management review process and in managing ongoing operations. “We have a corporate metrics dashboard that has a significant section dedicated to quality performance. The dashboard is compiled and monitored monthly by our senior, midlevel, and departmental managers,” said Le.

Nearly 30% of smaller start-up companies—those companies with up to $10 million in annual revenue—do not yet use quality metrics systematically in their management reviews. However, given the companies' emerging quality systems and stage of commercialization, this omission may be appropriate.

Those respondents who use quality metrics have clear goals and targets for their performance on key quality measures. The vast majority also have confidence in the data provided in their quality metrics. More than 80% said that their quality metrics accurately reflect the actual performance of their quality processes.

|

Figure 7. Generally, advanced performers shared responsibility for their quality |

As shown in Figure 6, companies that performed well in recent FDA inspections use performance metrics that are different from those of the general population. For example, the purpose of the metrics for advanced performers differs from that of companies with audit findings. More than 70% of advanced performers use quality metrics to assess progress and identify areas for continuous improvement. Less than half of companies that had audit findings use their quality metrics for such purposes.

In addition, advanced performers said that the quality organization plays a strong role in quality-related metrics. Most said that their quality departments manage the process of identifying and compiling quality metrics, while the other departments are responsible for performance on those metrics. This practice differs from what commonly happens in companies that reported audit findings. The majority of these companies said that each department is responsible for identifying and collecting its own quality performance metrics. Advanced performers have a centralized process for quality metrics, while companies with significant FDA audit findings have a distributed process for managing quality metrics.

Advanced performers also cited different practices in using metrics to manage partners and suppliers. They often use performance metrics to identify quality problems and drive process improvements with partners.

PRTM's experience with clients highlights a few additional practices that make metrics effective. First, focus is critical. The metrics should include a targeted set of high-level measures that tie into overall business objectives. Those high-level metrics can then cascade down to detailed metrics for different departments, though metrics proliferation should be carefully avoided. Second, quality metrics should be quite visible. Posting them on bulletin boards, providing an electronic metrics dashboard, and using them within management reviews are complementary means of sharing them and are more effective when used together. And third, responsibility for metrics must be clear. As demonstrated in the survey, broad responsibility for metrics performance helps promote a culture of quality throughout the organization.

Quality Policies and Procedures

|

Figure 6. Companies with no audit findings are more likely to use metrics with management reviews to measure performance and drive improvement (click to enlarge). |

Most survey takers use the FDA regulations as well as their own internal quality vision and inspection findings to drive the design of their quality systems. In addition, more than 70% believe their quality systems clearly align with the quality systems inspection technique (QSIT). FDA uses this approach to assess a medical device manufacturer's compliance with the quality system and related regulations.

Overall, most companies described their procedures as a hierarchy of linked documents. The linkages support overall process management, ensuring that processes flow across functions, such as manufacturing and R&D, and quality system processes, such as design control and document control. In addition, most agreed that their network of processes was easily adapted to support new products.

Here again, advanced performers differed from the general survey population. As shown in Figure 7, companies that performed well in recent FDA inspections cited the importance of ownership of quality policies and procedures across the entire company; each department took responsibility for its own processes. These companies also felt it was particularly important to align the quality processes with other internal business processes such as product development, human resources, and finance.

Just as in management oversight and review and performance management, partnership was a key theme of advanced performers in quality policies and procedures. The majority said that making sure policies and procedures stay aligned with those of their partners and suppliers was critical. Conducting periodic inspections of suppliers and partners, meeting with them when a change was proposed, and meeting immediately when problems arose maintained this crucial alignment. Contract manufacturers and emerging companies stressed the importance of partnerships. “As a contract manufacturer, our success depends on our ability to manage the quality of our product with our partners and key suppliers; therefore, we consider it a top priority to align our business practices and management structures to work in concert with our business partners,” explained Michael Hyatt, quality director at The Tech Group, a medical device contract manufacturer (Scottsdale, AZ).

Effective document change management is an essential element of quality systems. Advanced performers more often gave their quality groups the task of ensuring that changes to individual procedures are passed through to all other affected procedures. Many companies felt that making their quality group the clearinghouse for changes would ensure consistency across business processes. By contrast, companies that reported audit findings were more likely to rely on periodic inspections of their procedures or the change requestor to ensure that changes did not compromise linked documents.

Design and management of the quality system documentation is critical for efficient operations and ongoing compliance. The quality department can play an important role in defining the document hierarchy and the process framework. Other departments can then develop their procedures to fit within the overall framework. Having a clear framework ensures continuity across processes and efficient change control. At the same time, it allows individual departments to take responsibility for their own processes. This also simplifies communication with partners, making the quality system clear and easy to communicate.

Systems, Information, and Tools

More than 60% of survey participants said their companies have information systems in place for tracking customer complaints, nonconformances and corrective and preventive actions (CAPAs), equipment and maintenance, training, and product data management. Overall, about 40% of participants have customer relationship management (CRM) and enterprise resource management (ERP) systems in place.

Of all the different types of information systems, more than 80% of survey takers said their systems for customer complaints, nonconformances, and CAPAs were beneficial in managing quality performance. ERP and CRM systems were cited as the least helpful in managing quality. “ERP isn't really set up to manage quality, and we have found that CAPA and customer-complaints-tracking systems provide more direct support, as far as quality management is concerned,” explained Greg White, vice president of operations at PCI Technology (Dallas, TX).

The way advanced performers use their information systems to manage quality differs from those companies with audit findings. Advanced performers derive more value from their nonconformance and CAPA, equipment and maintenance, training, and product data management systems to manage quality.

In addition, advanced performers have clear corporate information technology strategies that include the infrastructure required to support management of quality systems. Information technology roadmaps accompany these strategies to illustrate how the systems infrastructure at these advanced companies will evolve over time and how the companies will invest in the infrastructure required to support this evolution.

Conclusion

Although survey respondents generally have solid baseline practices for quality systems, advanced performers employ numerous techniques to drive quality in their business. By aiming for excellence in quality throughout their companies, they need not worry about achieving baseline compliance. Their overall focus on quality automatically builds compliant practices as an inherent part of their organizations. In addition, they realize benefits beyond traditional quality measures.

Copyright ©2004 Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry

You May Also Like